Order a burger at Michigan's oldest tavern and you might be sitting where escaped slaves once hid from bounty hunters. Choose the wrong Coney Island restaurant in Detroit and half your family might disown you. These aren't just places to eat… they're time machines with menus, complete with family feuds, secret rooms, and recipes that survived Prohibition by pretending bourbon was root beer.

The pre-statehood survivors that refuse to quit

Michigan wasn't even officially Michigan yet when some of these places started slinging drinks and dinner. We're talking about restaurants so old they remember when Detroit to Chicago meant three days by stagecoach, not a budget flight you immediately regret booking.

The battle for "oldest" gets complicated

The Old Tavern Inn in Niles holds the official title as Michigan's oldest business still operating in its original building, though "original" requires some creative interpretation. Founded as Sumnerville Tavern in 1835, two years before Michigan achieved statehood, this place has changed hands 18 times across 189 years. The current owners, Kelli and Jason Vance, serve a Hot Ham Sandwich and Goulash that'll set you back a whopping $5.25, which honestly feels like time travel pricing too.

Here's where it gets weird: the original one-room log structure still exists, just buried beneath the current floor like some kind of architectural fossil. Oh, and the entire building was rotated 90 degrees in the mid-20th century because drivers kept smashing into the gas pumps. If you visit (Tuesday through Thursday from 11:30am-10:00pm, weekends til 11:00pm), you're literally standing above history at 61088 Indian Lake Road in Niles.

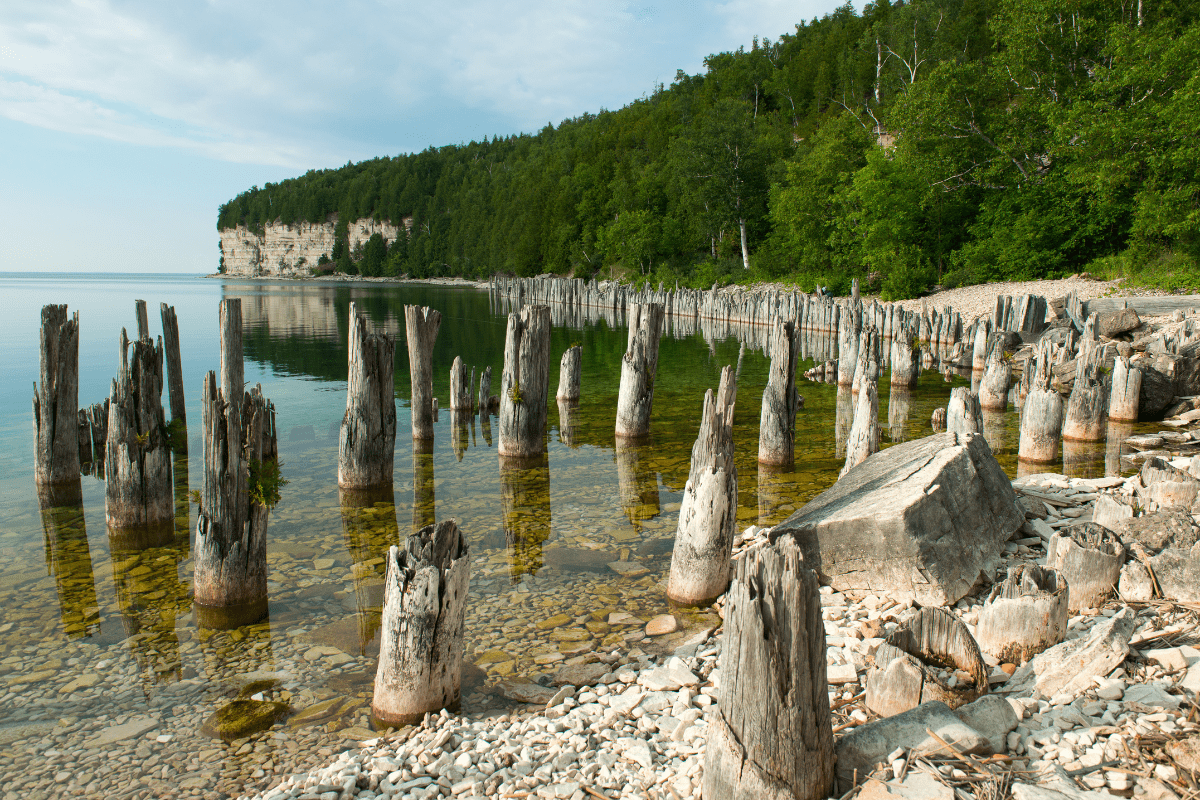

But wait, there's an older contender. The New Hudson Inn technically opened in 1831, making it four years senior to Old Tavern Inn. Russell Alvord got a 40-acre land grant signed by President Andrew Jackson himself, which is basically the 1830s version of getting verified on social media. The real story here isn't the age though… it's the hidden room above the main floor that sheltered escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad.

Current owner Chris "Stony" Stone (and yes, that's really his name) will show you this preserved chamber where you can still see clothes, coins, a corset box, and newspapers left behind by people fleeing to freedom. The inn at 56870 Grand River Avenue in New Hudson also features original hotel rooms with period wallpaper and a clawfoot tub, plus something called a spring-loaded dance floor that literally moved with the dancers. Your modern club with the light-up floor has nothing on 1800s engineering.

Then there's Sleder's Family Tavern in Traverse City, which plays a different card: they've never closed since 1882. Not once. Not for Prohibition, not for the Depression, not even for that really bad snowstorm in '78. Bohemian immigrant Vencil Sleder built it using wooden slabs from nearby sawmills, creating what's now home to a 21-foot solid mahogany bar that probably cost more than most people's cars.

The tradition here involves kissing Randolph the moose for luck, which sounds weird until you're three beers in and suddenly it makes perfect sense. During Prohibition, owner Louie Sleder served bourbon and rye in teacups, calling it "root beer" while winking so hard at law enforcement it's amazing he didn't pull a muscle. Current owners Ryan and Megan Cox (the fourth family to run it) continue serving the famous bean soup and host an all-you-can-eat fish fry every Friday after 5pm at 717 Randolph Street.

Detroit's delicious family drama

Some restaurants have history. Detroit's Coney Island restaurants have beef, and I don't just mean the hot dogs.

The feud that divided a city

The Keros brothers' split reads like a Greek tragedy, which makes sense since they were Greek immigrants. Constantine "Gust" Keros started American Coney Island in 1917 after working his way up from a hot dog cart. When his brother Bill arrived from Greece, they worked together until 1924, when a disagreement over chili recipes turned so bitter that Bill opened Lafayette Coney Island literally next door.

A century later, Detroiters still pledge loyalty to one side like it's a blood oath. The restaurants sit side by side at 114-118 W. Lafayette Boulevard, both serving natural-casing hot dogs with beanless chili, onions, and yellow mustard for about $3.75. Both stay open until 4am, feeding everyone from auto workers getting off third shift to Red Wings players celebrating victories. American stays in the Keros family under third-generation owner Grace Keros, while Lafayette sold to longtime employees in 1991.

Here's what makes this rivalry beautiful and insane: families have legitimate arguments about which Coney to support. Wedding planning has stalled over Coney preferences. First dates have ended when someone suggested the "wrong" restaurant. The hot dogs are nearly identical, but suggest that to a local and prepare for a 20-minute dissertation on why you're completely wrong.

When Roma became Amore

Detroit's Eastern Market tells a different story of preservation. Roma Cafe operated from 1890 to 2017 as Detroit's oldest Italian restaurant, with one fascinating footnote: a young chef named Hector Boyardi worked there before creating the Chef Boyardee empire. After 127 years, Roma finally closed, but former head chef Guy Pelino immediately rescued it, reopening as Amore da Roma with the same recipes and most of the same staff.

Located at 3401 Riopelle Street, they've kept Roma's Monday dinner buffet tradition while expanding the wine list from 20 to 100+ selections. Entrées run $18-35, reasonable for food that connects you to Detroit's Italian immigrant history. The restaurant maintains that old-school Italian-American vibe where the portions are huge, the sauce recipes are secret, and someone's grandmother would definitely approve.

Meanwhile, Jacoby's German Biergarten rounds out Detroit's immigrant restaurant scene with a love story. Albert Jacoby from Luxembourg married Minnie, a German cook from the prestigious Pontchartrain Hotel, with the business philosophy of "You'll cook, I'll handle the drinks, and hey, why not tie the knot while we're at it?" The building at 624 Brush Street dates to 1841 as a blacksmith shop, with painted signage from 1901 still visible on the south wall. They serve authentic schnitzel and sauerbraten with over 90 German beers, maintaining traditions in Detroit's rapidly evolving downtown.

The Polish places where pierogi are serious business

Detroit and Hamtramck's Polish restaurants don't mess around with authenticity, and they definitely don't mess around with portion sizes.

The Ivanhoe Cafe, known as the "Polish Yacht Club" despite being completely landlocked (Polish humor is wonderfully dry), opened in 1909 as a combination bar, gas station, and shoe store. They added a kitchen in the 1930s because apparently beer and shoe leather weren't a complete dining experience. Located on Joseph Campau in Detroit, current owners Patti Galen and daughter Tina Maks treat customers like family while maintaining a secret Prohibition-era basement room.

Polish Village Cafe in Hamtramck might be the most stubbornly traditional restaurant in Michigan. Founded in the mid-1970s by Ted and Frances Wietrzykowski, it occupies a basement at 2990 Yemans Street with true rathskeller atmosphere and a cash-only policy that feels like a personal challenge to the 21st century. Their daughter Carolyn maintains $8 entrée prices, which in 2025 dollars basically means they're paying you to eat.

The menu reads like a Polish grandmother's fever dream:

- Dill pickle soup (surprisingly addictive)

- Czarnina (duck blood soup)

- Five daily soup specials

- The Polish plate mega-meal

- Pierogi in multiple varieties

- Stuffed cabbage that could feed three

Recipes pass cook to cook through oral tradition rather than written instructions, like some kind of culinary folklore. This means each generation of cooks adds their own subtle touches while maintaining the core flavors that keep people coming back for decades.

Detroit's vanishing Chinatown

Here's a sadder story: Detroit's original Chinatown thrived from 1917 to the 1960s at Third Avenue and Porter Street, right where the MGM Grand Casino now stands. Urban renewal forced relocation to Cass Avenue and Peterboro, where Chung's Restaurant survived 60 years (1940-2000) as the longest-lasting Chinese establishment.

Today, only The Peterboro maintains a Chinese restaurant presence in the historic district, serving fusion cuisine while the city invests $1 million in streetscape improvements. It's a reminder that not all historic restaurants get happy endings, and sometimes whole communities' culinary traditions get paved over for progress.

The Upper Peninsula's mining and lumber legacy

The UP's historic restaurants tell stories of copper, timber, and the kind of cold that makes you question your life choices.

When beer built an empire

The Michigan House Cafe & Red Jacket Brewing Company in Calumet occupies a building that Joseph Bosch of Bosch Brewing Company built in 1905. By 1911, Bosch Brewing ranked as Houghton County's second-largest corporation after the copper mines, producing 50,000 barrels annually. This wasn't craft beer… this was "keeping miners happy" beer, which is arguably more important.

The building originally housed 26 hotel rooms and featured Michigan's most unnecessarily awesome beer tap, with flashing lights activated by each pull. Current owners Sue and Tim Bies have run it as a family brewpub for 23 years, hand-crafting Oatmeal Coffee Stout using 1905 recipe ingredients every Wednesday when they're closed to the public. They source beef from Frozen Farms in Calumet and potatoes from Johnson Brothers in Sagola, maintaining local connections that stretch back over a century.

The Vierling in Marquette, founded in 1883, sits just feet from Lake Superior's shoreline. One of Michigan's first brewpubs, it serves everything from artisan pizzas to filet mignon in a restored atmosphere with original stained glass and oil paintings. They're closed Sundays, probably because even historic restaurants need a day to recover from serving tourists asking if they can see Canada from here.

When mansions become menus

Some of Michigan's historic restaurants come with chandeliers, ghost stories, and the kind of atmosphere that makes you check if your shirt has stains.

The Whitney in Detroit transforms a Romanesque revival mansion into the city's most elegant dining experience. The Ghost Bar provides an upscale lounge experience with rumored supernatural activity, because apparently rich dead people also enjoy craft cocktails. Their afternoon tea service attracts visitors seeking a refined taste of Detroit's gilded age, when industrial barons built houses bigger than most modern schools.

The Holly Hotel, founded in 1891, exemplifies Queen Anne Victorian architecture while earning recognition on the US Register of Historic Places. After 133 years and 46 years under George and Chrissy Kutlenios' ownership, it recently went on the market. The Victorian French Onion Soup remains a signature dish that somehow tastes fancier than regular French onion soup, though I suspect it's the same soup in a fancier bowl.

The White Horse Inn in Metamora shows how historic preservation can work when someone throws $3 million at the problem. Built in 1848 as a general store and transformed into a stagecoach stop in 1850, it served Michigan Central Railroad passengers and allegedly operated as a Prohibition-era brothel (though every historic building claims this for marketing purposes).

After closing in 2012 due to deterioration, Victor Dzenowagis and Linda Egeland invested serious money in restoration, reopening in November 2014. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the inn now features igloo dining, because nothing says "historic preservation" like eating in a plastic bubble. Visit at 1 E High Street in Metamora for specialties including Cowboy Mac and Cheese and their famous Chicken Pot Pie.

How they survived everything history threw at them

These restaurants didn't make it 100+ years by accident. They survived by adapting, occasionally bending the law, and serving food so good people forgot there was a Depression happening.

During Prohibition, Detroit became America's bootlegging capital with 75% of illegal alcohol entering through the Detroit-Windsor corridor. Restaurants got creative: Old Tavern Inn became a grocery store, Sleder's served bourbon in teacups as "root beer," and New Hudson Inn repurposed Underground Railroad tunnels for liquor transport. Tommy's Detroit Bar operated a Purple Gang speakeasy in the basement, because if you're going to break federal law, might as well do it with style.

The Great Depression hit Michigan particularly hard, with Detroit serving 85,000 free meals daily at the crisis peak. Many restaurants operated as informal soup kitchens, with owners feeding neighbors on credit that would never be repaid. World War II brought rationing that forced "meatless menus" and creative substitutions, while women took over restaurant operations when men went overseas.

The COVID-19 pandemic became these restaurants' newest existential threat. The Michigan Restaurant Revitalization Fund provided $28.6 billion in support, while establishments got creative again. American Coney Island shipped Coney Kits nationwide, restaurants pivoted to grocery sales, and communities rallied with gift card campaigns that basically functioned as interest-free loans from loyal customers.

Planning your historic restaurant pilgrimage

Ready to eat your way through Michigan history? Here's what you need to know before your stomach takes a trip through time.

First, bring cash. Polish Village Cafe doesn't care about your Venmo, and several other historic spots maintain their cash-only policies like a badge of honor. Second, popular times require planning… Friday fish fries at Sleder's draw lines, and if you want a table at the Whitney on Valentine's Day, book it roughly around Christmas.

The weird hours are part of the charm. Detroit's Coney Islands serve until 4am because auto workers don't follow banker's hours. Some places close Mondays or Wednesdays seemingly at random. The New Hudson Inn will show you their Underground Railroad room, but maybe call ahead because "Stony" might be having a day.

Your historic restaurant starter pack

The must-visit classics:

- Kiss the moose at Sleder's

- Pick a Coney side forever

- Try Polish duck blood soup

- Find the Underground Railroad room

- Order the $5.25 goulash

These places generated part of Michigan's $54.8 billion tourism economy in 2024, proving that people will travel for food with a good story. They're living museums where you can eat the exhibits, family photo albums where the pictures smell like pierogi, and time machines where your ticket is a dinner check.

Every meal comes with ghosts… escaped slaves who found freedom, immigrants who found opportunity, families who built legacies one recipe at a time. These restaurants survived prohibition raids, economic collapses, urban renewal, and viral pandemics. They've hosted first dates, last suppers, wedding receptions, and midnight arguments about whose chili recipe was better.

So next time you're in Michigan, skip the chain restaurant and find one of these historic spots. Order something you can't pronounce, sit at a bar that's older than your great-grandmother, and become part of a story that's been unfolding for almost 200 years. Just remember: if someone asks whether you prefer American or Lafayette, that's not a casual question. That's a test of character, and there's no right answer, only consequences.