Georgia's ghost towns hold stories of gold rushes, industrial ambition, and vanished communities that shaped the American South. From Auraria's gold-fevered streets where America's first major gold rush began in 1832 to the underwater ruins of Petersburg beneath Lake Thurmond, these abandoned settlements offer visitors a haunting glimpse into the state's complex past.

The state harbors dozens of ghost towns across its 159 counties, ranging from completely submerged communities to partially preserved historic sites managed by the U.S. Forest Service. These abandoned places chronicle Georgia's evolution from Cherokee lands through the gold rush era, Civil War destruction, and the dramatic landscape changes of the 20th century when more than 40 man-made lakes flooded entire communities.

Unlike Western ghost towns that typically died when minerals ran out, Georgia's abandoned settlements tell more varied stories… religious utopias that failed, industrial towns destroyed by floods, and thriving ports bypassed by railroads. Lisa Russell, Georgia's foremost ghost town expert who teaches at Georgia Northwestern Technical College, puts it perfectly: "We look at something small and see how it made a big difference in the world."

Start with the one you can actually visit

Let's be honest: most ghost towns sit on private property where owners would rather greet you with buckshot than a welcome mat. That's why Scull Shoals Historic Site deserves top billing in your ghost town adventure plans.

Scull Shoals brings history without handcuffs

Located 15.5 miles from Greensboro in Greene County, this U.S. Forest Service site offers Georgia's most accessible ghost town experience. You can actually park your car, walk around freely, and take photos without worrying about angry landowners or trespassing charges. The GPS coordinates (33°43'17.89"N, 83°29'07.13"W) will lead you to a large parking area with interpretive signs and maintained trails.

Getting there from Atlanta requires about 90 minutes of increasingly rural driving. Take I-20 East to Exit 130, head north on GA 44 to Greensboro, then follow GA 15 north for 10.9 miles to Macedonia Church Road. Turn right and continue 2.4 miles to Forest Service Road 1234, then left for 1.8 miles to reach the site. Yes, you'll think you're lost at least twice, but trust the process.

Founded in 1782 as a frontier settlement, Scull Shoals evolved into something remarkable: home to Georgia's first paper mill in 1811. The state legislature even provided a $3,000 loan to Zachariah Sims and George Paschal for this pioneering venture, though it went bankrupt by 1815. Sometimes being first doesn't mean being successful.

Under Dr. Thomas Poullain's 41-year leadership starting in 1827, the town reached its zenith with over 600 residents and 500 mill workers tending 4,000 spindles. The massive Fontenoy Mills, rebuilt in brick after a devastating fire in 1846, consumed 4,000 cotton bales valued at $200,000 annually at peak production in 1854. The Oconee River's rapids provided reliable water power for gristmills, sawmills, cotton gins, and the four-story textile mill that dominated the landscape.

But here's where Mother Nature got the last laugh. Poor upstream farming practices caused severe soil erosion, gradually burying the rapids under silt. A series of floods in the 1880s culminated in the catastrophic flood of 1887, when water stood in buildings for four days, destroying equipment and ruining hundreds of cotton bales plus 600 bushels of wheat. The covered toll bridge swept downstream, never to be rebuilt. By the 1920s, everyone had given up and moved on.

Today, visitors can explore brick warehouse ruins with graceful arched windows, stone bridge foundations that once supported commerce, and the 2.5-mile Falling Creek Trail that winds through the historic area. The Forest Service maintains the site beautifully, making it perfect for photographers, history buffs, or anyone who wants to contemplate the temporary nature of human ambition.

Where gold fever created America's first boomtown

California likes to claim the gold rush, but Georgia got there first… by nearly two decades, actually.

Auraria earned its reputation the hard way

Founded in June 1832 in what's now Lumpkin County, Auraria exploded from wilderness to boomtown faster than you can say "there's gold in them thar hills." Within six months of William Dean building the first cabin, the town boasted 100 family dwellings, 20 stores, 15 law offices, and multiple taverns. By May 1833, the population hit 1,000 residents with 10,000 in the surrounding county. That's some serious growth for frontier Georgia.

The town earned the nickname "Knucklesville" for its frequent fist fights, while gambling houses and saloons operated around the clock. Vice President John C. Calhoun, who owned the nearby Calhoun Mine worked by enslaved laborers, gave the town its official name derived from the Latin word for gold, "aurum." Between 1829 and 1839, the area produced $20 million in gold, which is about $700 million in today's money if you're keeping score.

The party couldn't last forever. When Dahlonega became the county seat in 1833 and received the U.S. Branch Mint in 1838, businesses began relocating faster than prospectors abandoning a played-out claim. The 1849 California Gold Rush delivered the final blow as miners, including Green Russell who would later found another Auraria in Colorado (now part of Denver), abandoned Georgia for western goldfields.

Modern-day Auraria sits at the intersection of Auraria Road and Castleberry Bridge Road (GPS: 34°28'30"N, 84°1'24"W), but here's the crucial part: most of it's on private property. The current landowners don't mess around with trespassers, and local sources warn they'll pursue violators "aggressively." Translation: stay on the public roads and view from a distance unless you enjoy legal troubles.

What you can see from the road includes:

- Woody's General Store (closed since 1980s)

- The nearly collapsed Graham Hotel

- The 1840s Auraria Methodist Church

- A historical marker explaining the town's significance

- About 350 current residents living among the ruins

The Georgia Historical Society maintains excellent documentation about Auraria's role in American history, but they can't make the landowners any friendlier.

The underwater ghost towns nobody talks about

Here's something wild: Georgia has more ghost towns underwater than above ground, thanks to the Army Corps of Engineers' twentieth-century dam-building spree.

Petersburg vanished beneath the waves

Once Georgia's third-largest city… yes, you read that right… Petersburg now lies completely submerged beneath J. Strom Thurmond Lake (formerly Clarks Hill Lake) in Elbert County. Founded in 1786 by Revolutionary War veteran Dionysius Oliver at the confluence of the Broad and Savannah Rivers, the town thrived as a tobacco inspection and trading center.

Petersburg achieved remarkable political influence, becoming the only town in U.S. history to produce two simultaneous U.S. Senators: William Bibb and Charles Tait. The town's "Petersburg boats" carried 10 to 15 hogsheads of tobacco 60 miles downstream to Augusta, making it the Amazon fulfillment center of its day, minus the two-day delivery.

Property values tell the story of its rise and fall better than any historian could. Lot #81 sold for $2,500 in 1818 when the town boasted 750 permanent residents. By 1826, that same lot went for just $275. The town had a post office by 1795, the Georgia and Carolina Gazette newspaper by 1805, and absolutely nothing by 1950 when the waters rose.

The decline started when farmers abandoned tobacco for cotton production, which didn't require inspection stations. Without its primary economic purpose, Petersburg withered like week-old produce. Railroad lines bypassed the area entirely, and yellow fever outbreaks in the 1820s accelerated population loss. Only three families remained by 1854.

The town gained one final historical footnote when Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet crossed nearby during their 1865 retreat. Legend says they cast the Confederate seal into the Savannah River, though nobody's found it despite decades of searching by treasure hunters with more enthusiasm than sense.

During severe droughts, the lake level drops enough to reveal foundation stones and street patterns at Bobby Brown State Park. It's like archaeology for the impatient… just wait for a dry spell instead of digging.

Lisa Russell, author of "Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia," notes that Lake Allatoona alone has more identifiable underwater towns than all other North Georgia lakes combined. Her research reveals that more than 700 families were displaced just for Lake Lanier's creation. Progress has a price, and in Georgia, that price was entire communities.

When Sherman met the South's first company town

Not all ghost towns died quietly. Some went out in a blaze of, well, actual blazes.

Griswoldville shows what happens when industry meets war

Located 10 miles east of Macon in Jones County, Griswoldville represented one of the South's first true "company towns." Connecticut native Samuel Griswold founded the settlement in the 1840s, establishing a diversified manufacturing complex that produced cotton gins, farm implements, soap, candles, and furniture. The factory's location on the Central of Georgia Railway provided crucial transportation advantages.

The community included everything a nineteenth-century worker could want:

- A 24-room mansion for Griswold

- Worker cottages with gardens

- A nondenominational church

- Company store (naturally)

- About 500-600 residents at peak

When the Civil War began, Griswold partnered with A.N. Gunnison to convert the factory for Confederate weapons production. They manufactured approximately 3,700 brass-frame revolvers between 1862 and 1864… the highest production of any Confederate firearms manufacturer. These distinctive brass Colt Navy-style revolvers made Griswoldville a strategic Union target during Sherman's March to the Sea.

On November 20, 1864, Captain Frederick Ladd's 9th Michigan Cavalry destroyed the factories, burning the town twice just to make sure. But the real tragedy came two days later with the Battle of Griswoldville, the only major infantry engagement of Sherman's March.

Georgia militia consisting mostly of old men and teenage boys… nicknamed "Joe Brown's Pets" after the governor… made seven desperate charges against entrenched Union positions. The result was devastating: 650 Confederate casualties versus 62 Union losses. A Union officer reportedly said, "I hope we will never have to shoot at such men again." Even hardened soldiers recognized the senseless waste of sending untrained civilians against veteran troops.

The aged Samuel Griswold never rebuilt, and though about 80 people remained by 1900, the town essentially died with its factories. Today, Georgia maintains 17 acres as a state historic site with interpretive markers explaining the battle and the town's industrial significance.

Planning your ghost town expedition without getting shot or arrested

Let's talk practical matters, because getting arrested for trespassing really ruins the Instagram aesthetic.

Best times to channel your inner explorer

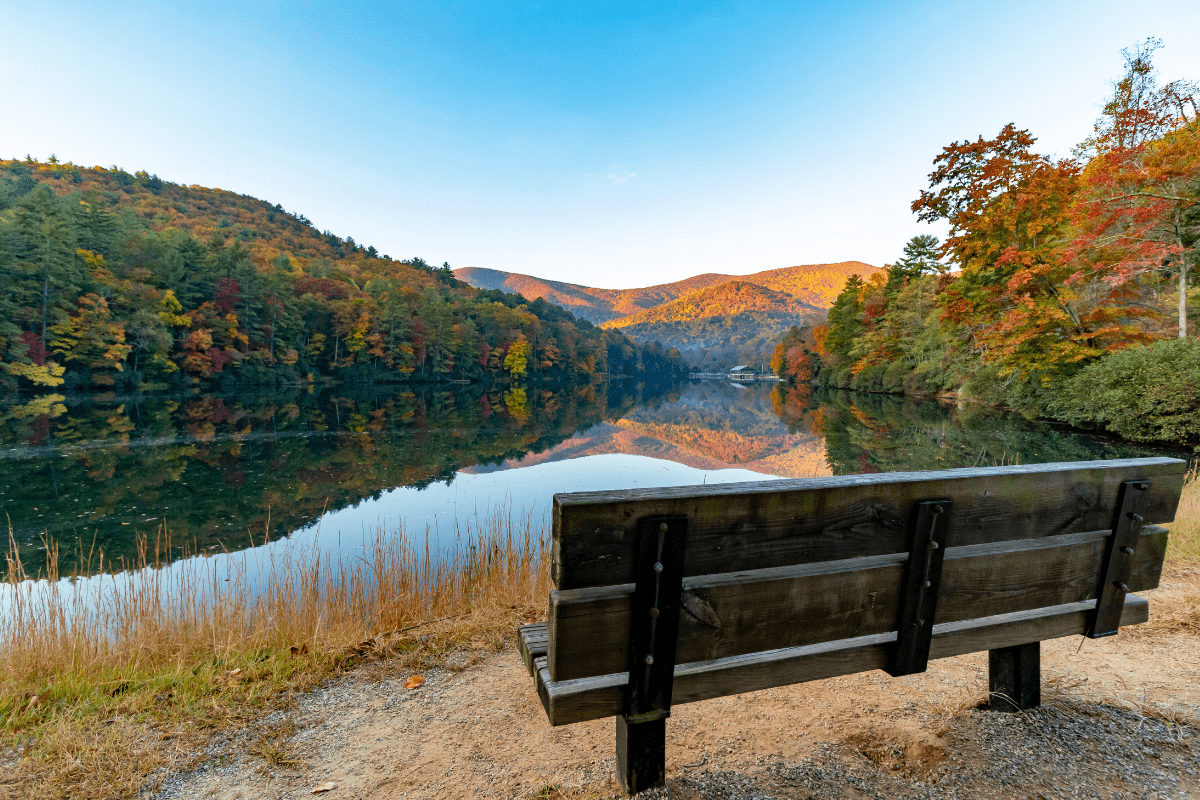

Fall offers the optimal ghost town hunting season, specifically September through November. Temperatures range from 55-75°F, humidity drops to bearable levels, and the foliage provides stunning backdrops for photos. October particularly attracts ghost town enthusiasts for Halloween-themed explorations, though you're more likely to encounter other tourists than actual ghosts.

Spring (March through May) works too, but Georgia's pollen will coat everything… your car, your camera, your soul… in yellow dust. Summer means oppressive heat, aggressive mosquitoes, and increased snake activity. Winter's actually not bad if you don't mind bare trees and the occasional cold snap.

Essential gear that might save your day

Nobody wants their ghost town adventure to end in the emergency room, so pack accordingly:

- Sturdy hiking boots (not sneakers)

- Long pants for snake protection

- First aid kit with antihistamine

- More water than you think

- Downloaded offline maps

- Portable phone charger

- Bug spray (lots of it)

- Flashlight for ruins exploration

Georgia hosts six venomous snake species, including Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes and Copperheads, who don't care about your vacation plans. Cell phone coverage remains spotty in remote areas… AT&T provides the best coverage at 99.6% statewide, though many ghost town locations lack any signal. Tell someone where you're going and when you'll be back. Seriously.

The legal stuff nobody wants to discuss

Georgia's criminal trespass laws carry penalties up to 12 months in jail and $1,000 fines. Most ghost towns sit on private property where owners actively monitor for trespassers. Auraria landowners are particularly known for aggressive enforcement. Local sources aren't joking about the buckshot.

Even publicly accessible sites prohibit artifact removal under federal law. That rusty nail or broken bottle might seem like a cool souvenir, but it's actually evidence of historical significance. Take photos, not artifacts. Besides, do you really want a possibly cursed object from a ghost town in your house? That's how horror movies start.

The preservation efforts keeping history alive

Not every ghost town has to stay ghostly forever. Several communities have found new life through creative preservation efforts.

Success stories worth celebrating

New Echota, the former Cherokee Nation capital, operates as a fully accessible state historic site and museum. Juliette got saved by the 1991 film "Fried Green Tomatoes" and now thrives as a weekend tourist destination with operating restaurants and shops. Sometimes Hollywood does more for preservation than a hundred historians.

The Jerusalem Lutheran Church at Ebenezer, completed in 1769, maintains the oldest continuously operating Lutheran congregation in the United States. Wrightsboro, a 1768 Quaker settlement, still has its Methodist church standing proud despite the town disappearing around it.

Universities are getting involved too. The University of Georgia and Georgia State University both offer Master of Historic Preservation programs, training the next generation of professionals who'll hopefully be better at saving towns than our ancestors were at abandoning them. In 2020, Georgia State conducted geophysical surveys at Scull Shoals, searching for the Revolutionary War-era Fort Clarke using technology that would seem like magic to the town's original residents.

How regular people can help

The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation, founded in 1973 with over 8,000 members, maintains an annual "Places in Peril" list and operates grant programs. They've distributed more than $3.5 million in matching funds since 1994. Wright Mitchell, the Trust's president, warns that "climate change and associated natural disasters present the biggest threat to historic resources," particularly affecting coastal archaeological sites threatened by storm surge and erosion.

You don't need a history degree to make a difference:

- Join the Georgia Trust

- Document sites through photography

- Support heritage tourism businesses

- Respect private property boundaries

- Share stories on social media

- Visit state historic sites

The ghost towns still worth mentioning

A few more abandoned communities deserve recognition, even if we can't visit them all. Ebenezer Creek marks the site of a tragic 1864 incident during Sherman's March where freed slaves were abandoned at a destroyed bridge. Many drowned trying to cross or were recaptured by Confederate cavalry… a dark chapter often omitted from Civil War narratives.

The towns under Lake Lanier displaced 700 families and several communities, creating what some call "Georgia's haunted lake." During droughts, church steeples and foundations emerge like something from a horror movie. Local legends about the lake's supernatural properties probably stem from the knowledge that entire communities lie beneath boats and swimmers.

Embracing the impermanence

Georgia's ghost towns represent more than mere abandonment… they embody the dynamic forces that shaped the American South. From religious utopias to industrial powerhouses, from gold rush boomtowns to underwater monuments to progress, these sites offer tangible connections to pivotal moments in American history.

Whether you're exploring the accessible ruins at Scull Shoals, viewing Auraria from a respectful (and legal) distance, or waiting for drought conditions to reveal Petersburg's bones, you're encountering stories of ambition, tragedy, and transformation that continue to resonate across centuries. These places remind us that nothing lasts forever, not even entire towns, and maybe that's what makes them so fascinating.

So grab your hiking boots, respect the property lines, and go explore what remains of Georgia's forgotten communities. Just remember: take only pictures, leave only footprints, and always assume the landowner has buckshot.